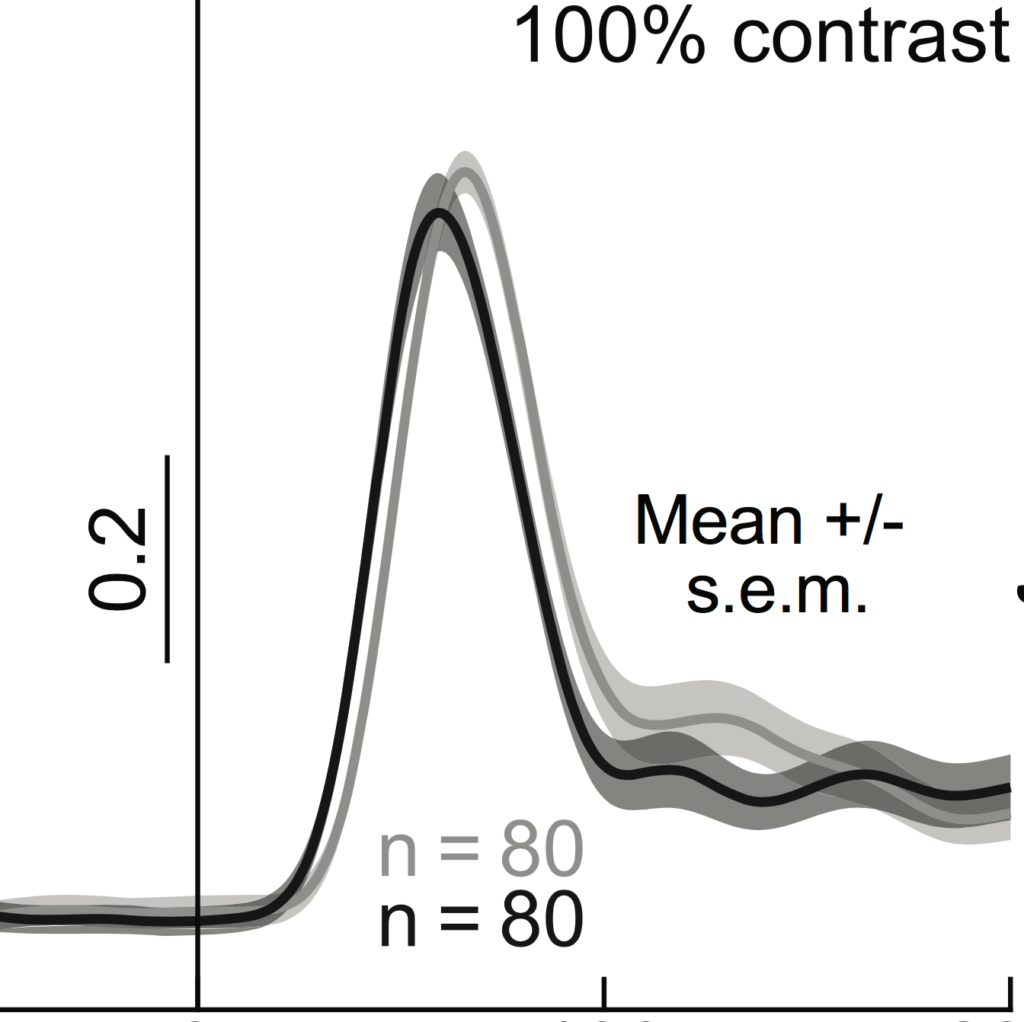

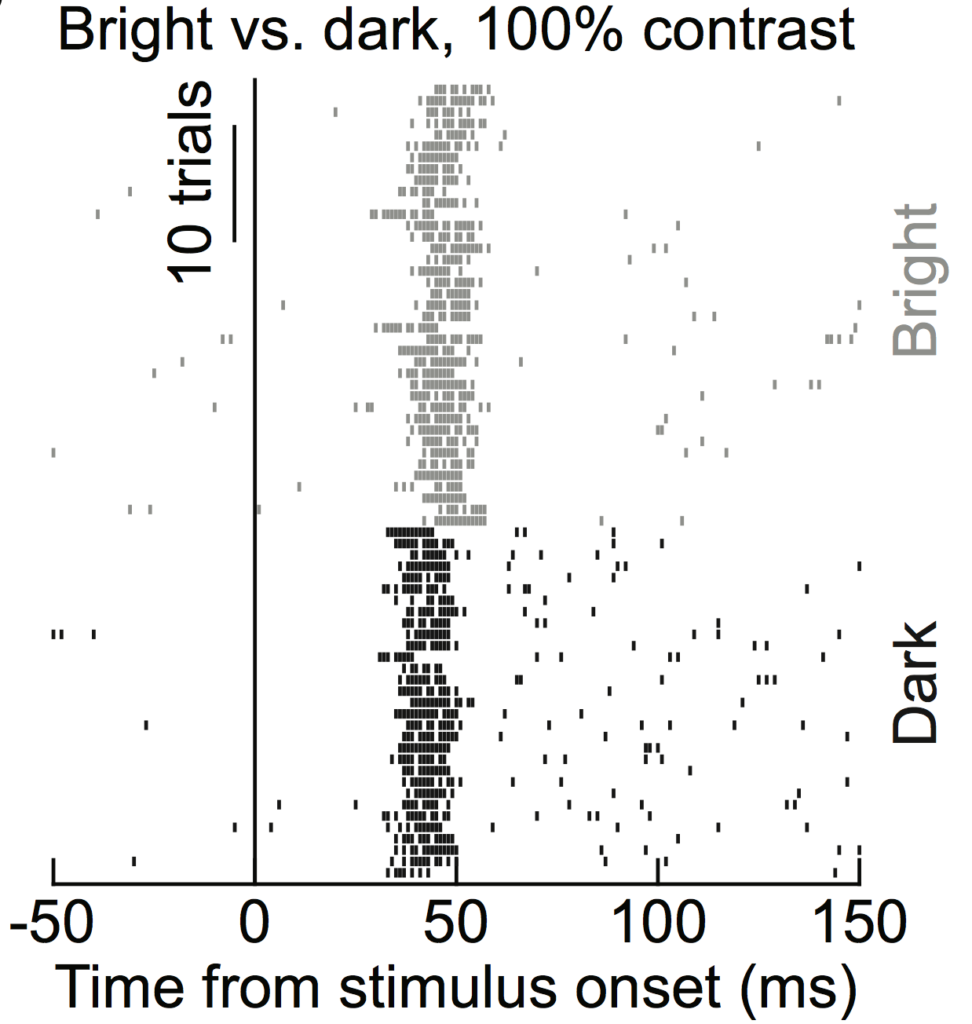

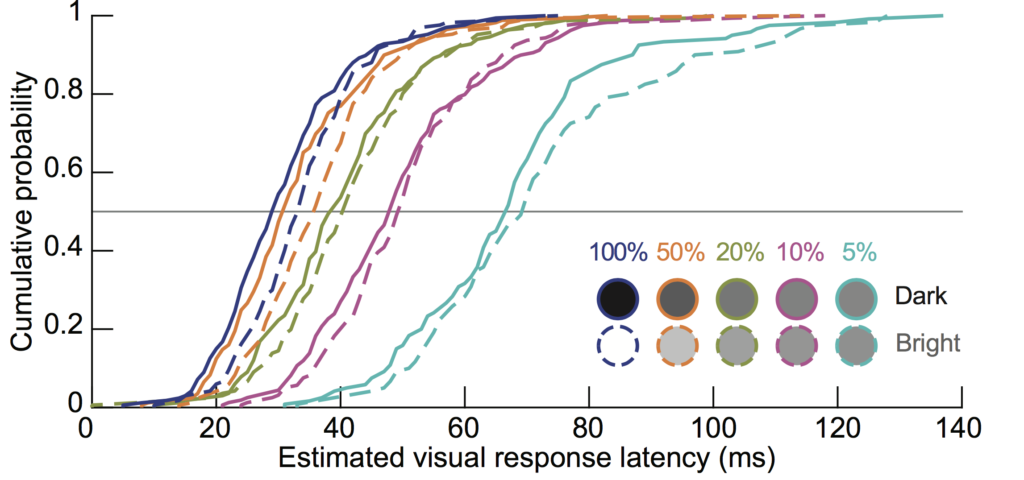

We have a new paper just published in the Journal of Neuroscience. In it, we observed that superior colliculus (SC) visual responses occur faster for stimuli that are darker, rather than brighter, than the background.

Interestingly, this faster detection of dark stimuli occurs even if a neuron is more sensitive to bright stimuli. That is, one normally expects that if a neuron is more sensitive to a given stimulus (i.e. having a stronger visual response to it), then its response to the stimulus also occurs faster. However, here we found a dissociation: a neuron could be more sensitive to bright stimuli (emitting a stronger response), but it still responds earlier to dark stimuli. It is interesting that we previously also saw such a dissociation between visual response sensitivity and response latency in the SC, but in the context of spatial frequency processing instead (Chen et al., 2018). It would be interesting in the future to model such dissociation.

In our study, we also presented stimuli of different contrasts. At each contrast that we tested, visual responses occurred earlier for dark than bright stimuli. However, there were also additional interesting interactions between contrast sensitivity and the faster detection of darks in the SC. For example, we previously found that the SC processes upper visual field images very differently from lower visual field images (Hafed & Chen, 2016). In our current study, the faster detection of dark contrasts was amplified in the upper visual field, consistent with a strong and multi-faceted anisotropy in how the SC represents upper and lower visual field image locations.

Our results are interesting because they demonstrate that the SC may be sensitive to the ecological likelihood of dark versus bright contrasts in natural scenes. For example, an object flying above us during the day tends to cast a dark shadow on our retina, as opposed to shining bright light. Indeed, we found that eye movements can indeed occur faster for dark than bright contrasts. Our results are also interesting because they demonstrate that the SC, while it receives primary visual cortex input, is not simply inheriting its visual response properties from the cortex. Rather, it recomputes image information in a manner that is suitable for orienting behaviors.

Our future work will relate these SC visual response properties to eye movement behavior in more detail, and it will also explore how eye movement commands in the SC may be sensitive to whether a stimulus is bright or dark. So, stay tuned!