We have a new paper just published in the Journal of Neuroscience. In this paper, we investigated visual field anisotropies, but specifically when visual stimuli appeared in the temporal vicinity of rapid saccadic eye movements.

Past work has shown that visual perceptual performance is either the same or significantly better (depending on the stimulus conditions) in the lower visual field than in the upper visual field. That is, when not moving our eyes, we tend to perform better for stimuli appearing below our current line of sight. This can have an ecological basis, since peri-personal space (e.g. food that we can grasp and bring to our mouth) tends to be below our current line of sight.

On the other hand, the “oculomotor” system (i.e. brain structures controlling eye movement generation but still exhibiting visual sensation) seems to better represent the upper visual field, which can help in remote sensing. For example, in previous work, we found a large preference for the upper visual field in the visual neural sensitivity and spatial resolution of superior colliculus neurons.

This raises an intriguing question about how vision operates around the time of saccades. As is well known, even though perception is suppressed around the time of saccades (e.g. see here and here), it is not completely abolished. There is still residual visual sensitivity. So, the question becomes: does vision in the fleeting moments around saccadic eye movements follow the sensitivity bias that it normally exhibits (i.e. preferring the lower visual field) in the absence of saccades, or does it mimic the preference of the oculomotor system for the upper visual field?

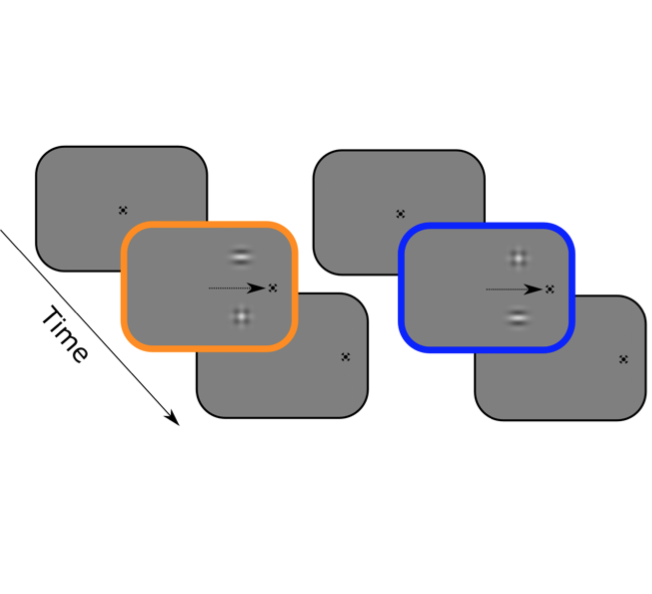

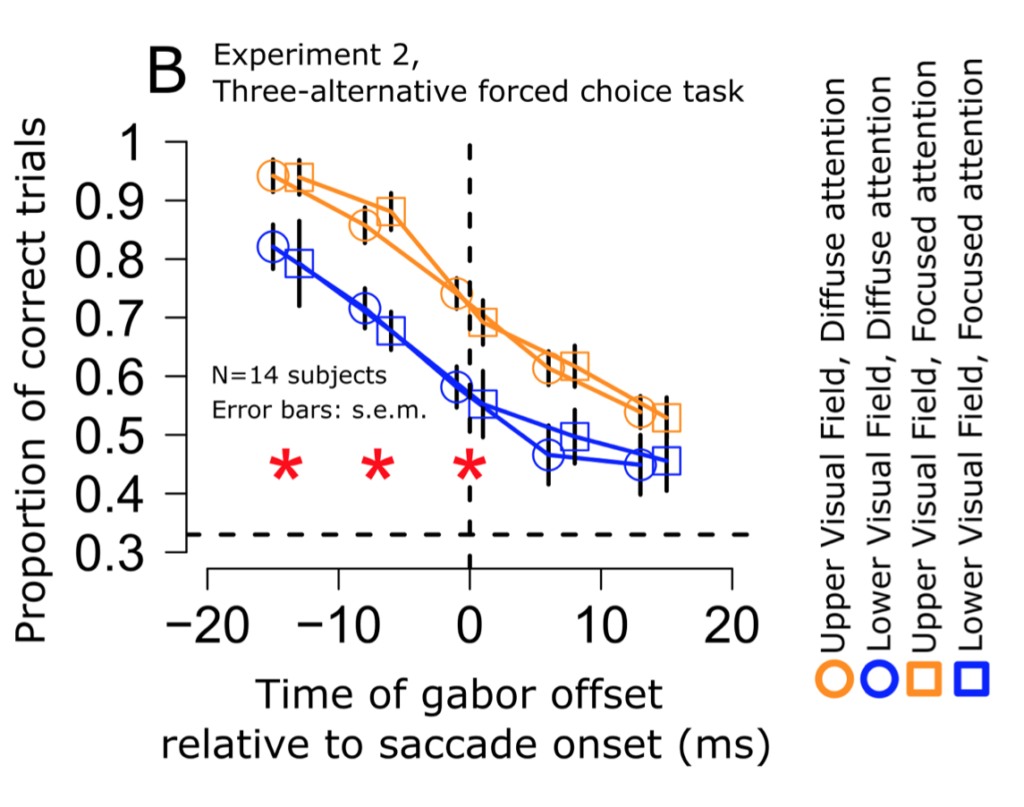

We first started with psychophysical experiments in human subjects. We asked these subjects to make horizontal saccades, and we tested their perceptual performance for stimuli in the upper or lower visual fields. We carefully controlled possible confounding factors like the retinal positions of the stimuli, and so on.

Across several experiments, we found that the subjects “saw” better in the upper visual field! That is, their perceptual performance mimicked the preference of the so-called “oculomotor” system rather than the “visual” system (i.e. in the absence of eye movements).

We next asked whether our observations were trivially explained by our experimental setup. That is, maybe something in our setup caused visual performance to be somehow better in the upper visual field, irrespective of eye movements. If so, then we would still see better performance in the upper visual field even when trying to replicate the classic experiments in the absence of eye movements. We, thus, ran control experiments with gaze fixation and no saccades. We replicated the classic observations that vision is better or the same (depending on the stimulus properties) in the lower visual field rather than in the upper visual field. Thus, our peri-saccadic observations were categorically different from the known performance of vision in the absence of rapid eye movements.

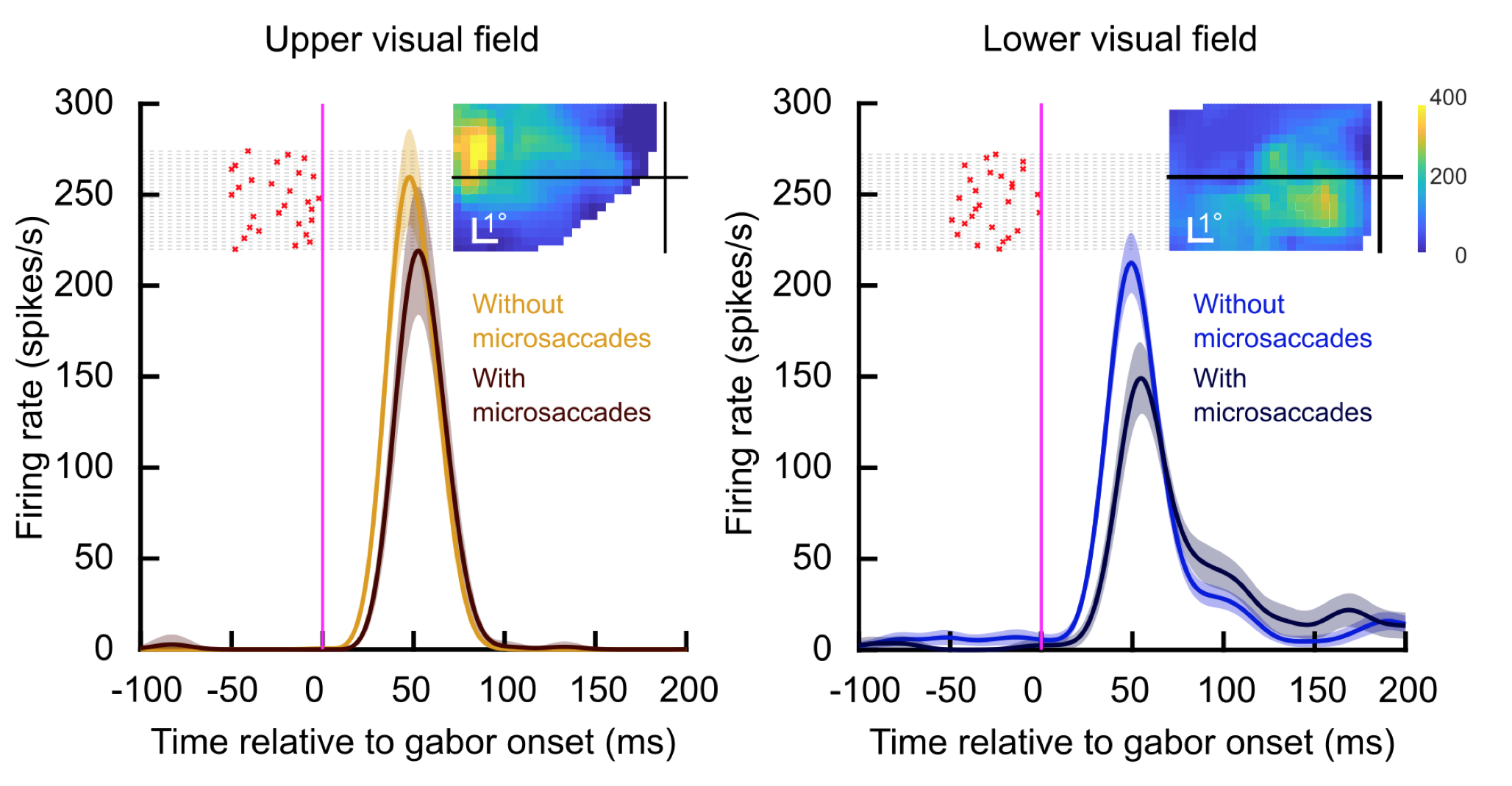

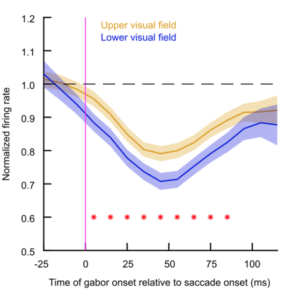

Finally, we then moved to neurophysiology. We asked whether peri-saccadic visual sensitivity in the superior colliculus still preferred the upper visual field. This was indeed the case: even though the visual sensitivity of superior colliculus neurons was suppressed for peri-saccadic stimuli, the suppression was significantly weaker for neurons representing the upper visual field. Thus, we observed that peri-saccadic superior colliculus visual neural sensitivity was again higher in the upper visual field.

Our results motivate many future experiments related to how different brain areas (e.g. primary visual cortex and superior colliculus) can coordinate their activity to guide behavior even when they may intrinsically exhibit exactly opposite representational anisotropy (e.g. one area preferentially processing the lower visual field and the other area preferentially processing the upper visual field). Stay tuned for more efforts from us on that front!